Difference between revisions of "Samuel Pierpont Langley"

(report from artillery corps) |

(add some info from Adler) |

||

| (16 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | '''Samuel P. Langley''' ( | + | '''Samuel P. Langley''' (1834–1906) was an astronomer and early aviation experimenter. He made telescopes and observed planets at a young age. After graduating from Boston High School he went to work as a telescope maker and then as an astronomy at Harvard College Observatory, the U.S. Naval Academy, the Western University of Pennsylvania, and Allegheny Observatory. His interests included Sun observations and time standardization, as enabled by astronomy. In 1887 he became secretary of the [[Smithsonian]]. From 1887–1895 he worked on successive designs for his heavier-than-air "aerodrome". In 1895 (or 1896?) he conducted two successful trials and received a $50,000 grant from the [[U.S. War Department]]. However, over the next decade, his machines could not fly reliably.<ref>[https://library.si.edu/staff/william-baxter William E. Baxter], "[http://www.sil.si.edu/ondisplay/langley/intro.htm Samuel P. Langley: Aviation Pioneer]", ''Smithsonian'', 1999?</ref><ref>"[http://sova.si.edu/record/NASM.XXXX-0494?q=samuel+langley&s=0&n=10&i=0 Samuel P. Langley collection]", ''Smithsonain'' (finding aid).</ref> |

| − | Langley's | + | According to contemporary journalist Mark Sullivan, Langley intended to retire after the trials of 1896 but was prevailed upon to continue by the [[War Department]].<ref>[[Sullivan, 1927, Our Times]], p. 558.</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | Langley used flat, rather than cambered, aeroplanes in his experiments, partly because he wanted to investigate the physical principles applying to a plane moving through air. (See [[Francis Herbert Wenham]] and the revision to Newton's law.) Like Wenham he used a [[whirling arm]] to test models. Langley's whirling arm was mounted 8 feet high and surrounded by an octagonal fence; the end of the arm moved at 70mph. Once Langley established his experimental protocol he assigned much of the work to assistants [[Frank W. Very]] and [[Joseph Ludewig]].<ref>[[Crouch, 1981]], pp. 47–52.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Aerodrome A]] broke in 1903 trials, resulting in some scandal and pessimism from the project's backers.<ref>[[Hallion, 2003]], pp. 155–156. "After the Arsenal Point fiasco, an understandably chastened Federal government refused to make any further appropriations for the Langley effort, and what little military ardor for heavier-than-air flight as had existed noticeably cooled. The final War Department report on the ''Great Aerodrome'' dishearteningly concluded: 'The claim that an engine-driven man-carrying Aerodrome has been constructed lacks the proof which actual flight alone can give. . . . We are still far from the ultimate goal, and it would seem as if years of constant work and study by experts, together with the expenditure of thousands of dollars, would still be necessary before we can hope to produce an apparatus of practical utility.' Predictably, Congressional response was quick and damning, chiding the War Department for supporting the project and ridiculing Langley for his obsession with flight. Congressman Gilbert Hitchcock of Nebraska stated, 'The only thing [Langley] ever made fly was Government money.'"</ref> The U.S. Artillery Corps reported: "The unfortunate accidents have prevented any test of the apparatus in these flights and the claim that an engine-driven man-carrying aerodrome has been constructed lacks proof, which actual flight alone can give."<ref>[[Guggenheim, 1930, The Seven Skies]], pp. 39–40.</ref> Langley's assistant [[Cyrus Adler]] later said the criticism overwhelmed Langley: "At his years, for he was then nearly seventy, the attitude assumed by the public press broke his spirit at this the first, indeed the only, defeat in his career."<ref>[[Adler, 1907, Samuel Pierpont Langley]], p. [https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=chi.65432771&view=1up&seq=26 20].</ref> | ||

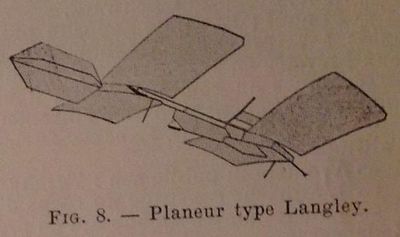

[[File:Planeur type Langley.jpg|400px|center|Langley Glider]] | [[File:Planeur type Langley.jpg|400px|center|Langley Glider]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | The fact that Langley was researching aviation encouraged others to take the field seriously. He wrote in ''[[Langley, 1891, Experiments in Aerodynamics|Experiments in Aerodynamics]]'' (1891): "The mechanical sustenation of heavy bodies in the air, combined with very great speeds, is not only possible, but within the reach of mechanical means we already possess."<ref>[[Randers-Pehrson, 1944]], p. 312. "The fact that Langley, an internationally famous scientist, engaged in aeronautical research, was a great encouragement to aviation enthusiasts. It helped to make flying machine experiments a respectable pursuit, not necessarily indicative of an unbalanced mind."</ref> | ||

=== References === | === References === | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

| − | {{ | + | === Publications === |

| − | + | * [[Langley, 1891, Experiments in Aerodynamics]] | |

| − | {{ | + | * [[Langley, 1897, The "Flying–Machine"]] |

| + | * [[Langley, 1908, Researches and Experiments in Aerial Navigation]] (Smithsonian) | ||

| + | * [[Langley Memoir on Mechanical Flight, 1911]] (Smithsonian) | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Person | ||

| + | |Names=Samuel Pierpont Langley; Samuel Langley; Professor Langley; Langley | ||

| + | |Birth date=1834-08-22 | ||

| + | |Death date=1906-02-27 | ||

| + | |Countries=US | ||

| + | |Locations=Boston, Massachusetts; Pittsburgh; Washington DC | ||

| + | |Occupations=astronomer; director; aviation experimenter; scientist | ||

| + | |Tech areas=wings; lift; aeroplane | ||

| + | |Affiliations=Smithsonian Institution; University of Pittsburgh; War Department; American Philosophical Society; Royal Society | ||

| + | |Wikidata id=Q357961 | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Standard person reports|Samuel Pierpont Langley}} | ||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category: Authors]] |

| + | [[Category: Scientists]] | ||

Latest revision as of 14:36, 28 December 2023

Samuel P. Langley (1834–1906) was an astronomer and early aviation experimenter. He made telescopes and observed planets at a young age. After graduating from Boston High School he went to work as a telescope maker and then as an astronomy at Harvard College Observatory, the U.S. Naval Academy, the Western University of Pennsylvania, and Allegheny Observatory. His interests included Sun observations and time standardization, as enabled by astronomy. In 1887 he became secretary of the Smithsonian. From 1887–1895 he worked on successive designs for his heavier-than-air "aerodrome". In 1895 (or 1896?) he conducted two successful trials and received a $50,000 grant from the U.S. War Department. However, over the next decade, his machines could not fly reliably.[1][2]

According to contemporary journalist Mark Sullivan, Langley intended to retire after the trials of 1896 but was prevailed upon to continue by the War Department.[3]

Langley used flat, rather than cambered, aeroplanes in his experiments, partly because he wanted to investigate the physical principles applying to a plane moving through air. (See Francis Herbert Wenham and the revision to Newton's law.) Like Wenham he used a whirling arm to test models. Langley's whirling arm was mounted 8 feet high and surrounded by an octagonal fence; the end of the arm moved at 70mph. Once Langley established his experimental protocol he assigned much of the work to assistants Frank W. Very and Joseph Ludewig.[4]

Aerodrome A broke in 1903 trials, resulting in some scandal and pessimism from the project's backers.[5] The U.S. Artillery Corps reported: "The unfortunate accidents have prevented any test of the apparatus in these flights and the claim that an engine-driven man-carrying aerodrome has been constructed lacks proof, which actual flight alone can give."[6] Langley's assistant Cyrus Adler later said the criticism overwhelmed Langley: "At his years, for he was then nearly seventy, the attitude assumed by the public press broke his spirit at this the first, indeed the only, defeat in his career."[7]

The fact that Langley was researching aviation encouraged others to take the field seriously. He wrote in Experiments in Aerodynamics (1891): "The mechanical sustenation of heavy bodies in the air, combined with very great speeds, is not only possible, but within the reach of mechanical means we already possess."[8]

References

- ↑ William E. Baxter, "Samuel P. Langley: Aviation Pioneer", Smithsonian, 1999?

- ↑ "Samuel P. Langley collection", Smithsonain (finding aid).

- ↑ Sullivan, 1927, Our Times, p. 558.

- ↑ Crouch, 1981, pp. 47–52.

- ↑ Hallion, 2003, pp. 155–156. "After the Arsenal Point fiasco, an understandably chastened Federal government refused to make any further appropriations for the Langley effort, and what little military ardor for heavier-than-air flight as had existed noticeably cooled. The final War Department report on the Great Aerodrome dishearteningly concluded: 'The claim that an engine-driven man-carrying Aerodrome has been constructed lacks the proof which actual flight alone can give. . . . We are still far from the ultimate goal, and it would seem as if years of constant work and study by experts, together with the expenditure of thousands of dollars, would still be necessary before we can hope to produce an apparatus of practical utility.' Predictably, Congressional response was quick and damning, chiding the War Department for supporting the project and ridiculing Langley for his obsession with flight. Congressman Gilbert Hitchcock of Nebraska stated, 'The only thing [Langley] ever made fly was Government money.'"

- ↑ Guggenheim, 1930, The Seven Skies, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Adler, 1907, Samuel Pierpont Langley, p. 20.

- ↑ Randers-Pehrson, 1944, p. 312. "The fact that Langley, an internationally famous scientist, engaged in aeronautical research, was a great encouragement to aviation enthusiasts. It helped to make flying machine experiments a respectable pursuit, not necessarily indicative of an unbalanced mind."

Publications

- Langley, 1891, Experiments in Aerodynamics

- Langley, 1897, The "Flying–Machine"

- Langley, 1908, Researches and Experiments in Aerial Navigation (Smithsonian)

- Langley Memoir on Mechanical Flight, 1911 (Smithsonian)

| Names | Samuel Pierpont Langley; Samuel Langley; Professor Langley; Langley |

|---|---|

| Countries | US |

| Locations | Boston, Massachusetts, Pittsburgh, Washington DC |

| Occupations | astronomer, director, aviation experimenter, scientist |

| Tech areas | Wings, Lift, Aeroplane |

| Accreditations | |

| Affiliations | Smithsonian Institution, University of Pittsburgh, War Department, American Philosophical Society, Royal Society |

| Family name | |

| Birth date | 1834-08-22 |

| Death date | 1906-02-27 |

| Wikidata id | Q357961 |

This person had 52 publications and 0 patents in this database.

Publications by or about Samuel Pierpont Langley

- Langley, 1891, Expériences d'aérodynamique (Simple title: Aerodynamic experiences, Journal: Rev. Aér.)

- Langley, 1891, Recherches expérimentales aérodynamiques et données d'expérience (1) (Simple title: Aerodynamic experimental research and experimental data, Journal: L'Aéronaute)

- Langley, 1891, Recherches expérimentales aérodynamiques et données d'expérience (2) (Simple title: Aerodynamic experimental research and experimental data, Journal: C. R. Acad. Sci.)

- Langley, 1891, Recherches expérimentales aérodynamiques et données d'expérience (3) (Simple title: Aerodynamic experimental research and experimental data, Journal: C. R. Acad. Sci.)

- Langley, 1891, Recherches expérimentales aérodynamiques et données d'expérience. Review by O. Lilienthal (Simple title: Aerodynamic experimental research and experimental data. Review by O. Lilienthal, Journal: Zeitschr. Luftsch.)

- Langley, 1891, Experiments in aerodynamics (1) (Simple title: Experiments in aerodynamics (1), Journal: Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge)

- Drzewiecki, 1891, De la concordance des résultats expérimentaux de M. S.-P. Langley sur la résistance de l'air, avec les chiffres obtenus par le calcul (Simple title: The concordance of the experimental results of M. S.-P. Langley on the air resistance, with the figures obtained by calculation, Journal: Rev. Aér.)

- Langley, 1891, The possibility of mechanical flight (Simple title: The possibility of mechanical flight, Journal: Century Mag.)

- Langley, 1892, Mechanical flight (Simple title: Mechanical flight, Journal: Cosmopolitan)

- Maxim, 1892, Progress in Aerial Navigation (Simple title: Progress in aerial navigation, Journal: Fortnightly Review)

- Langley, 1893, Le travail intérieur du vent (Simple title: The internal work of the wind (6), Journal: Rev. Aér.)

- Langley, 1894, Internal work of the wind. A paper read before the National Academy of Sciences, and the Aeronautical Congress at Chicago (Simple title: Internal work of the wind. A paper read before the National Academy of Sciences, and the Aeronautical Congress at Chicago, Journal: Scient. Amer. Suppl.)

- Clayton, 1894, The Eddy Malay tailless kite (Simple title: The Eddy Malay tailless kite, Journal: Scient. Amer.)

- Langley, 1894, Die innere Arbeit des Windes (Simple title: The inner work of the wind, Journal: Naturwissenschaftliche Rundschau)

- Langley, 1894, The internal work of the wind (1) (Simple title: The internal work of the wind (1), Journal: Amer. Journ. Sci.)

- Langley, 1894, The internal work of the wind (2) (Simple title: The internal work of the wind (2), Journal: Engineering News)

- Langley, 1894, The internal work of the wind (3) (Simple title: The internal work of the wind (3), Journal: London, Edinburgh and Dublin Philos. Mag.)

- Langley, 1894, The internal work of the wind (4) (Simple title: The internal work of the wind (4), Journal: Proceedings of the conference on aerial navigation, Chicago, 1893 • Aeronautics)

- Marvin, 1894, The internal work of the wind. Discussion of Professor Langley's paper (Simple title: The internal work of the wind. Discussion of Professor Langley's paper, Journal: Proceedings of the conference on aerial navigation • Aeronautics)

- Means, 1894, The problem of manflight (Simple title: The problem of manflight)

- Langley, 1894, Théorie du vol à voile (Simple title: Theory of gliding, Journal: L'Aéronaute)

- Langley, 1895, Langley's law (Simple title: Langley's law, Journal: Aeronautical Annual)

- Langley, 1896, A successful trial of the aerodrome (Simple title: A successful trial of the aerodrome, Journal: Science)

- Langley, 1896, Description du vol mécanique (1) (Simple title: Description of mechanical flight (1), Journal: C. R. Acad. Sci.)

- Langley, 1896, Description du vol mécanique (2) (Simple title: Description of the mechanical flight (2), Journal: C. R. Acad. Sci.)

- Langley, 1896, Experiments in mechanical flight (Simple title: Experiments in mechanical flight, Journal: Nature)

- Langley, 1896, Lettre de M. Samuel Pierpont Langley à l'Académie des Sciences (Simple title: Letter from Mr. Samuel Pierpont Langley to the Academy of Sciences, Journal: L'Aéronaute)

- Publication 7202, 1896, L'aéroplane de M. Samuel Pierpont Langley (Simple title: Samuel Pierpont Langley's aeroplane, Journal: L'Aéronaute)

- Langley, 1897, A rubber-propelled model (Simple title: A rubber-propelled model, Journal: Aeronautical Annual)

- Langley, 1897, Langley, Samuel Pierpont. Story of experiments in mechanical flight (Simple title: Langley, Samuel Pierpont. Story of experiments in mechanical flight, Journal: Aeronautical Annual)

- Publication 5638, 1897, Langley's Flugmaschine (Simple title: Langley's flying machine, Journal: Ill. Aër. Mitt.)

- Langley, 1897, Methods of launching aerial machines (Simple title: Methods of launching aerial machines, Journal: Aeronautical Annual)

- Huffaker, 1897, On soaring flight (Simple title: On soaring flight, Journal: Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution)

- Publication 7217, 1897, Samuel Pierpont Langley (Simple title: Samuel Pierpont Langley, Journal: Aeronautical Annual)

- Langley, 1897, Story of experiments in mechanical flight (Simple title: Story of experiments in mechanical flight, Journal: Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution)

- Langley, 1897, The Flying Machine (Simple title: The Flying Machine, Journal: McCure's Mag.)

- Langley, 1897, The new flying machine (Simple title: The new flying machine, Journal: Strand Mag.)

- Maxim, 1898, Flying Machines and Ordnance (Simple title: Flying machines and ordnance, Journal: Scient. Amer. Suppl.)

- Langley and Lucas, 1901, The greatest flying creature. Introducing a paper by F. A. Lucas (Simple title: The greatest flying creature. Introducing a paper by F. A. Lucas, Journal: Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution)

- Langley, 1901, The Langley aerodrome: Note for the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, 1901 (Simple title: The Langley aerodrome: Note prepared for the Conversazione of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, 1901, Journal: Smithsonian Report)

- Publication 464, 1902, Airship contest rules (Simple title: Airship contest rules, Journal: Aer. World)

- Publication 1862, 1902, Birds as models and Mr. Benbow on Prof. Langley. (Simple title: Birds as models and Mr. Benbow on Prof. Langley, Journal: Aer. World)

- Publication 7201, 1902, Dr. Langley's aerodynamic experiments (Simple title: Dr. Langley's aerodynamic experiments, Journal: Aer. World)

- Langley, 1902, Experiments in aërodynamics (2) (Simple title: Experiments in aërodynamics (2))

- Publication 7215, 1902, Professor Langley's new experiments (Simple title: Professor Langley's new experiments, Journal: Aër. Journ.)

- Langley, 1902, Story of experiments in mechanical flight (Simple title: Story of experiments in mechanical flight, Journal: Aer. World)

- Edison tells Dumont to get rid of balloons, 1902 (Simple title: Edison Tells Dumont to get Rid of Balloon)

- Publication 7206, 1903, Langley on the problem of flying (Simple title: Langley on the problem of flying, Journal: Aer. World)

- Publication 7208, 1903, Langley's Experimente (Simple title: Langley's Experimente, Journal: Wien. Luftsch. Zeit.)

- Publication 7214, 1903, Professor Langley's Flugschiff (Simple title: Professor Langley's airship, Journal: Ill. Aër. Mitt.)

- Publication 7213, 1903, Professor Langley's airship model (Simple title: Professor Langley's airship model, Journal: Aër. Journ.)

- Hoernes, 1903, Die Luftschiffahrt der Gegenwart (Simple title: The airship of the present)

- Publication 4307, 1903, The Failure of Langley's aerodrome (Simple title: The Failure of Langley's aerodrome, Journal: Scient. Amer.)

- Langley, 1903, The greatest flying creature (Simple title: The greatest flying creature, Journal: Aer. World)

- Langley, 1904, Experiments with the Langley aerodrome (1) (Simple title: Experiments with the Langley aerodrome, Journal: Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution)

- Langley, 1904, Greatest flying creature (Simple title: Greatest flying creature, Journal: Scient. Amer. Suppl.)

- Publication 7203, 1904, Langley (Simple title: Langley, Journal: Ill. Aër. Mitt.)

- Langley, 1905, Experiments with the Langley aerodrome (2) (Simple title: Experiments with the Langley aerodrome, Journal: Scient. Amer. Suppl. • Nature)

- Castagneris, 1905, L'Istituto speciale di aerodinamica di Koutchino (Simple title: The special institute for aerodynamics at Koutchino and the worldwide technical development of aerodynamics, Journal: Bollettino della Società Aeronautica Italiana)

- Moedebeck, 1906, Samuel Pierpont Langley (Simple title: Samuel Pierpont Langley, Journal: Ill. Aër. Mitt.)

- Publication 7218, 1906, Samuel Pierpont Langley (Simple title: Samuel Pierpont Langley, Journal: Boll. Soc. Aer. Ital.)

- Newcomb, 1906, Side-lights on astronomy and kindred fields of popular science (Simple title: Side lights on astronomy and kindred fields of popular science)

- Newcomb, 1906, Side-lights on astronomy and kindred fields of popular science (Simple title: Side lights on astronomy and kindred fields of popular science)

- Publication 130, 1906, The Aero Club of America's exhibits recently shown at the Sixth Annual Automobile Show (Simple title: The Aero Club of America's aeronautical exhibits recently shown at the Sixth Annual Automobile Show in New York City, Journal: Scientific American)

- Dienstbach, 1907, Practical air craft (Simple title: Practical air craft, Journal: Nav. the Air)

- Adler, 1907, Samuel Pierpont Langley (Simple title: Samuel Pierpont Langley)

- Adler, 1907, The aeroplane experiments of the late Professor Langley (Simple title: The aeroplane experiments of the late Professor Langley, Journal: Aer. Journ.)

- Langley, 1908, Experiments with the Langley aerodrome (3) (Simple title: Experiments with the Langley aerodrome, Journal: Pop. Sci. Monthly)

- Publication 7205, 1908, Langley machine to be flown. Langley's memoirs (Simple title: Langley machine to be flown. Langley's memoirs, Journal: Aeronautics)

- Publication 7204, 1908, Langley. A tribute (Simple title: Langley. A tribute, Journal: Scient. Amer.)

- Langley, Adler, and Lucas, 1908, Researches and experiments in aerial navigation, Reprinted from the Smithsonian reports (Simple title: Researches and experiments in aerial navigation, Reprinted from the Smithsonian reports)

- Publication 5416, 1908, The government dirigible and dynamic flyer (Simple title: The government dirigible and dynamic flyer, Journal: Amer. Mag. Aeronautics)

- Langley, 1908, The internal work of the wind (5) (Simple title: The internal work of the wind (5), Journal: Contr. Knowl.)

- Wrights, 1908, The Wright Brothers' aeroplane (Simple title: The Wright Brothers' aeroplane, Journal: Century Mag.)

- Hunter, 1909, Samuel Pierpont Langley (Simple title: Samuel Pierpont Langley, Journal: Fly)

- Langley, 1910, Photograph and biography of S. P. Langley (Simple title: Photograph and biography of S. P. Langley, Journal: Aircraft)

- Langley, 1910, The internal work of the wind (Simple title: The internal work of the wind, Journal: Aircraft)

- Bell, 1910, The pioneer of aerial flight. The work of Samuel Pierpont Langley (Simple title: The pioneer of aerial flight. The work of Samuel Pierpont Langley, Journal: Scient. Amer. Suppl.)

- Ventou-Duclaux and Robert, 1911, Bases et méthodes d'études aéronautiques (Simple title: Bases et méthodes d'études aérontechniques)

- Langley and Manly, 1911, Langley memoir on mechanical flight (Simple title: Langley memoir on mechanical flight, Journal: Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge)

- Langley, 1911, Langley's book on aviation. A classic in practical aerodynamics (Simple title: Langley's book on aviation. A classic in practical aerodynamics, Journal: Scient. Amer. Suppl.)

- Langley, 1913, Prof. Langley's memory honored (Simple title: Prof. Langley's memory honored, Journal: Aero and Hydro)

- Langley, 1914, Dr. Langley, discoverer of the air (Simple title: Dr. Langley, discoverer of the air, Journal: Literary Digest)

- Besio Moreno, 1914, Historia de la Navegación Aérea (Simple title: History of Aerial Navigation, Journal: Anales de la Sociedad Científica Argentina)

- Langley, 1914, Langley harnessing the air (Simple title: Langley harnessing the air, Journal: Motor Print)

- Langley, 1914, Langley's aviation work reviewed (Simple title: Langley's aviation work reviewed, Journal: Aero and Hydro)

- Langley, 1914, Samuel P. Langley's work may affect the future history of aviation (Simple title: Samuel P. Langley's work may affect the future history of aviation, Journal: Aero and Hydro)

- MacDonald, 1914, Samuel Pierpont Langley (Simple title: Samuel Pierpont Langley, Journal: The Integral)

- Langley, 1915, Did Langley fly? (Simple title: Did Langley fly?, Journal: Aeronautics)

- Langley, 1915, Samuel Pierpont Langley (Simple title: Samuel Pierpont Langley, Journal: Aircraft • Aeronautics)

- Langley, 1916, Birthplace of aviation (Simple title: Birthplace of aviation, Journal: Aerial Age)

- Brewer, 1921, The Langley Machine and the Hammondsport Trials (Simple title: The Langley Machine and the Hammondsport Trials, Journal: Journal of the Royal Aeronautical Society)

- Crouch, 1981 (Simple title: A Dream of Wings)

Letters sent by Samuel Pierpont Langley

Letters received by Samuel Pierpont Langley