Difference between revisions of "Clément Ader"

(Zahm's opinion of the Avion III "fiasco") |

(more from Zahm) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | '''Clément Agnès Ader''' ( | + | '''Clément Agnès Ader''' (2 April 1841 – 3 May 1925) was a aero inventor and electrical engineer from Muret (near Toulouse), credited by some with the first successful airplane flight. |

After graduating from the Institution Assiot, a specialized engineering school in Toulouse, he went to work for a railroad company. Then he began designing vélocipèdes and formed the company Véloces-Caoutchouc Clément Ader.<ref>[[Hallion, 2003]], p. 127.</ref> | After graduating from the Institution Assiot, a specialized engineering school in Toulouse, he went to work for a railroad company. Then he began designing vélocipèdes and formed the company Véloces-Caoutchouc Clément Ader.<ref>[[Hallion, 2003]], p. 127.</ref> | ||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

Ader successfully solicited support from the French military and designed more aircraft in 1891–1892: the ''[[Avion II]]'' a.k.a. ''Zéphyr'' and the ''[[Avion III]]'' a.k.a. ''Aquilon''. On 3 February 1892 he optimistically signed a 550,000 contract to provide the military with a heavier-than-air bomber which could travel at 35 miles per hour. He brought forth a craft in 1897 and demonstrated it in October. It didn't fly. Ader was quietly cut off.<ref>[[Hallion, 2003]], pp. 133–134.</ref> | Ader successfully solicited support from the French military and designed more aircraft in 1891–1892: the ''[[Avion II]]'' a.k.a. ''Zéphyr'' and the ''[[Avion III]]'' a.k.a. ''Aquilon''. On 3 February 1892 he optimistically signed a 550,000 contract to provide the military with a heavier-than-air bomber which could travel at 35 miles per hour. He brought forth a craft in 1897 and demonstrated it in October. It didn't fly. Ader was quietly cut off.<ref>[[Hallion, 2003]], pp. 133–134.</ref> | ||

| − | ([[Albert Francis Zahm|Zahm]] blames this "fiasco" on bad weather and inexperience. "In truth," he writes, "Avion No. 3 was hardly, if at all excelled in airframe design by the first prize-winner planes of Santos-Dumont, Farman, and some others.")<ref>[[Zahm, 1944]], p. | + | ([[Albert Francis Zahm|Zahm]] blames this "fiasco" on bad weather and inexperience. "In truth," he writes, "Avion No. 3 was hardly, if at all excelled in airframe design by the first prize-winner planes of Santos-Dumont, Farman, and some others.")<ref name=Zahm>[[Zahm, 1944]], p. 342–345.</ref> |

[[Samuel P. Langley]] visited Ader's workshop in July and August 1899. Langley got along well with Ader but didn't think much of his airplane: "The 'Avion' is simply a gigantic bat, plus steam engine and propellers . . . It seemed to me that the 'Avion', as constructed, had no chance of moving in the air for a single minute without disaster."<ref>Langley Papers, box 27, quoted in [[Hallion, 2003]], p. 135.</ref> | [[Samuel P. Langley]] visited Ader's workshop in July and August 1899. Langley got along well with Ader but didn't think much of his airplane: "The 'Avion' is simply a gigantic bat, plus steam engine and propellers . . . It seemed to me that the 'Avion', as constructed, had no chance of moving in the air for a single minute without disaster."<ref>Langley Papers, box 27, quoted in [[Hallion, 2003]], p. 135.</ref> | ||

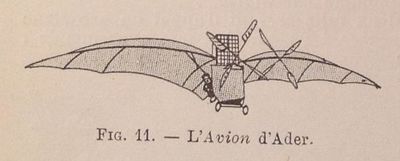

[[File:L'Avion d'Ader.jpg|400px|center|File:L'Avion d'Ader.jpg]] | [[File:L'Avion d'Ader.jpg|400px|center|File:L'Avion d'Ader.jpg]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ader destroyed his euipment and records in 1903.<ref name=Zahm /> | ||

Ader later wrote a popular book called [[Ader, 1908, L'Aviation militaire|L'Aviation militaire]] ("Military Aviation"; 1908, followed by multiple editions), as well as another one called [[Ader, 1907, La Première Étape de l'aviation militaire française|La Première Étape de l'aviation militaire française]] ("The First Stage of French Military Aviation"; 1907). | Ader later wrote a popular book called [[Ader, 1908, L'Aviation militaire|L'Aviation militaire]] ("Military Aviation"; 1908, followed by multiple editions), as well as another one called [[Ader, 1907, La Première Étape de l'aviation militaire française|La Première Étape de l'aviation militaire française]] ("The First Stage of French Military Aviation"; 1907). | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1930, France erected a monument to Ader at his birthplace, proclaiming him "Père de l'Aviation".<ref name=Zahm /> | ||

{{Compact patent list|{{PAGENAME}}}} | {{Compact patent list|{{PAGENAME}}}} | ||

Revision as of 21:11, 30 November 2017

Clément Agnès Ader (2 April 1841 – 3 May 1925) was a aero inventor and electrical engineer from Muret (near Toulouse), credited by some with the first successful airplane flight.

After graduating from the Institution Assiot, a specialized engineering school in Toulouse, he went to work for a railroad company. Then he began designing vélocipèdes and formed the company Véloces-Caoutchouc Clément Ader.[1]

Ader began work on aviation after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. First he created an unsuccessful human-powered ornithopter. This vessel weighed 20 kg (with no pilot) and had wing surface of 9 m².[2]

Then he began work on gliders but didn't follow through and went into electricity and the emerging telephone. This paid off well, but he maintained his interest in aeronautics, traveling to Strasbourg to study storks and Algeria (where he met Louis-Pierre Mouillard) to study vultures. In 1895 he hired Éloi Vallier and Louis Espinosa as assistants. By 1890 they had constructed a vessel—an early airplane—called Éole, featuring bat-shaped wings and a 20-horsepower engine constructed in-house.[3] The Éole was tested on 9 October 1890 might have lifted off the ground a little on a runway. Zahm and others consider this to be the first successful airplane flight.[4] Ader much later made an unproven claim that he had flown at Satory in September 1891.[3]

Ader successfully solicited support from the French military and designed more aircraft in 1891–1892: the Avion II a.k.a. Zéphyr and the Avion III a.k.a. Aquilon. On 3 February 1892 he optimistically signed a 550,000 contract to provide the military with a heavier-than-air bomber which could travel at 35 miles per hour. He brought forth a craft in 1897 and demonstrated it in October. It didn't fly. Ader was quietly cut off.[5]

(Zahm blames this "fiasco" on bad weather and inexperience. "In truth," he writes, "Avion No. 3 was hardly, if at all excelled in airframe design by the first prize-winner planes of Santos-Dumont, Farman, and some others.")[6]

Samuel P. Langley visited Ader's workshop in July and August 1899. Langley got along well with Ader but didn't think much of his airplane: "The 'Avion' is simply a gigantic bat, plus steam engine and propellers . . . It seemed to me that the 'Avion', as constructed, had no chance of moving in the air for a single minute without disaster."[7]

Ader destroyed his euipment and records in 1903.[6]

Ader later wrote a popular book called L'Aviation militaire ("Military Aviation"; 1908, followed by multiple editions), as well as another one called La Première Étape de l'aviation militaire française ("The First Stage of French Military Aviation"; 1907).

In 1930, France erected a monument to Ader at his birthplace, proclaiming him "Père de l'Aviation".[6]

Patents applied for by Clément Ader

- Patent FR-1880-132944

- Patent FR-1890-205155

- Patent FR-1891-205155.1

- Patent FR-1894-205155.2

- Patent FR-1897-271948

- Patent FR-1898-205155.3

- Patent FR-1898-271948.1

- Patent FR-1898-271948.2

- Patent FR-1898-278138

- Patent FR-1898-278138.1

Letters sent by Clément Ader

- Clément Ader to Gabriel de La Landelle 13 June 1883

- Clément Ader to Henry Farman 21-Oct-1908

- Clément Ader to M. le Président 12-Oct-1908

- Clément Ader to Nadar 12-Oct-1890

Letters received by Clément Ader

References

- ↑ Hallion, 2003, p. 127.

- ↑ Lissarrague, 1990, Clément Ader, pp. 45–48.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Hallion, 2003, pp. 128–131. "This airplane—the first in history, though certainly unsuccessful—featured a lightweight 20-horsepower steam engine of his own design, powerful enough (producing one horsepower per ten pounds of engine weight, a remarkable figure for the day) to propel it off level ground. Therefore, despite the lack of success he shared with all pre-Wright predecessors, Ader is due all credit for inventing the first significant powered airplane."

- ↑ Zahm, 1944, pp. 330, 336 etc.

- ↑ Hallion, 2003, pp. 133–134.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Zahm, 1944, p. 342–345.

- ↑ Langley Papers, box 27, quoted in Hallion, 2003, p. 135.