Dominguez Field exhibition

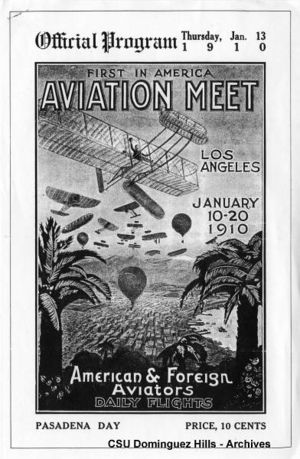

The Dominguez Field exhibition, held in January 1910 near Los Angeles, was the first major aero exhibition in the United States.

Promotion

After Glenn Hammond Curtiss won the Gordon Bennett trophy at the Reims Air Meet, the next meet by rule was to be held in the United States. (Planning for the event began after Curtiss flew at the St. Louis Centennial Week in October 1909.)[1] Curtiss used this momentum to promote the Dominguez Field event, billed as the first air meet in the U.S. [2][3] The Aviation Committee was Dick Ferris (chariman), Cortlandt F. Bishop, Edwin Cleary, and Jerome S. Fancuilli.[4]

The meet was organized by the Merchants and Manufacturers Association; David A. Hamburger was committee chairman; Percy W. Weidner (treasurer) and Lynden E. Behymer in charge of ticket sales; other committee members Fred L. Baker, Martin C. Neuner, Dick Ferris, William May Gardlin, and Felix J. Zeehandelarr (secretary). Joseph and Edward Carson permitted use of the field.[5]

One promoter of the meet was newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, who advertised for the event in the Los Angeles Examiner and at the exhibition ground set up a tethered balloon stating "It's all in the Examiner."[2] The Los Angeles Times was another sponsor.[6][7] The meet was also promoted as a fashion event for women.[8]

Aviators

Star pilots attending included Curtiss and Louis Paulhan, both of who were facing lawsuits by the Wright Brothers for patent infringement. (A judge in New York enabled the meet to take place by postponing their court date until afterwards.)[9] Curtiss won fastest speed at 43.9 mph. LTA dirigibles had their own events but, travelling at less than 20mph, were perceived to be outperformed by airplanes.[2] Also participating: Charles F. Willard, flying a Curtiss Golden Flier, and Roy Knabenshue, flying a dirigible balloon.[10] See below for full results.

Aviators flew Farman, Voisin, and Blériot model aircraft. Including specifically: Farman II, Blériot XI, Blériot XII.[11] Paulhan broke a height record on January 12 by ascending to 4165 in a biplane. Charles K. Hamilton flew across the U.S. Mexico border to Tijuana and returned after 40 minutes having flown 34 miles.[5]

Spectators could see some more unusual aircraft as well, including creations by Prof. J. S. Zerbe (an apparatus with a complex frame supporting five big aeroplanes), Prof. H. LaV. Twining (human-powered ornithopter), Jacob Klassen (monoplane with vertical fin), and Edgar Smith with "the rowboat that had sprouted wings".[12]

Attendees

About 20,000 people attended the meet each day it was open.[2] Total visitors, 176,000.[5] Thousands sat in a big wooden grandstand, with regularly spaced American flags, watching the show.[13]

Lietenant Paul W. Beck made a report for the U.S. Signal Corps to analyze the possibilities of a balloon attack in San Pedro Harbor. About the same subject, a journalist (?) observed on January 14:[5]

"If airships should ever be employed for warlike purposes and it is possible they may have to be used just once in order to teach the world the most terrible lesson of its history, they will render helpless and obsolete all the warships. Naval programs may as well be abandoned. A mercantile fleet carrying armed aeroplanes will be more than a match for any war fleet.

On the 19th a newspaper stated: "Interest in the army maneuvers was heightened when it became known that the Hague Peace Tribunal had just issued a bulletin asking all nations to sign an agreement which will make the throwing of bombs from aeroplanes 'unpermissible' in war."[5]

Paulhan took William Boeing for a ride.[2] Future aviation inventor and air force general Jimmy Doolittle also attended.[14]

Effect

The airshow is considered by some to have kickstarted the aeronautics industry in Southern California and inspired more such airshows throughout the Southwest. Good weather in January suggested the local climate's conduciveness to year-round aviation.[6][7]

Curtiss took (some of?) the first aerial photographs from heavier-than-air craft, using a Heart camera attached to the Curtiss Flyer.[15]

In December 1910, the Charity Aviation Corporation secured a 5-year lease for annual meets on Dominguez field. Only two were held: one in December 1910, one in 1912.[16]

- ; >56 aircraft (Berliner says only 16 though 43 were entered)[2]; $75K in prizes ; 254,000 tickets sold ; gate receipts of $137,500; $50,000 guaranteed pay for Paulhan[5]

Results

Pauley, 2009, p. 99:

<bockquote>On the afternoon of January 20, the 11th and final day of the meet, and before any flying activities could take place, a parade with the theme "From Ox-cart to Airplane" was staged. A farewell ceremony followed, where D. A. Hamburger, chairman of the Aviation Committee, expressed his appreciation to the participants and announced the prizewinners and runners-up:

Speed, 10 laps (16.11 miles): $3,000, Glenn Curtiss, 23:43 3/5, first; $2,000, Louis Paulhan, 24:59 2/5, second; $500, Charles Hamilton, 30:34 3/5, third. Endurance and Time: $3,000, Paulhan, 75.77 miles, 1:52:32, first; $2,000, Hamilton, 19.44 miles, 39:00 2.5, second; $500, Curtiss (same time as speed), third. Altitude: $3,000, Paulhan, 4,165 feet, first; $2,000, Hamilton, 330.5 feet, second; no prize money, Curtiss with no official height taken, third. Three laps with a passenger: $1,000, Paulhan, 4.83 miles, 8:16 1/5, no others contested. Slowest lap (1.61 miles): $500, Hamilton, 3:32 (27 miles per hour average). Fastest lap (1.61 miles): $500, Curtiss, 2:12 (43.9 miles per hour average). Shortest Distance Takeoff: $250, Curtiss, 98 feet. Quickest Time Takeoff, $250, Curtiss, 6.4 seconds. Accuracy: $250, Charles Willard, starting from a 20-foot square, making a circuit of the course, and landing in the same square. Solo Cross-country: $10,000, Paulhan, to Santa Anita and return, 45.1 miles, 1:2:42 1/5. Cross-country with passenger: no prize money, Paulhan with Celeste Paulhan, to Redondo Beach and return, 21.25 miles.

References

- ↑ J. Wesley Neal, "America's First International Air Meet", Historical Society of Southern California Quarterly, December 1961.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Don Berliner, "The Big Race of 1910", Air & Space Magazine (Smithsonian), January 2010.

- ↑ Pauley, 2009, pp. 9, 21.

- ↑ Pauley, 2009, p. 102.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Marco R. Newmark, "The Aviation Meet of 1910", The Quarterly: Historical Society of Southern California 28(3), September 1946.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Roger D. Launius and Jessie L. Embry, "Fledgling Wings: Aviation Comes to the Southwest, 1910-1930", New Mexico Historical Review 70(1), 1995.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Hunter Hollins, "Science and Military Influences on the Ascent of Aerospace Development in Southern California", Southern California Quarterly 96(4), 2014.

- ↑ Pauley, 2009, p. 29. "A cartoon depicts a crowd of hatted, fashionably dressed women whose faces are turned upward. Air meet sponsors wanted to increase female attendance, so promoting fashionable clothing for Aviation Week was a smart move on the part of advertisers."

- ↑ Pauley, 2009, p. 31.

- ↑ Pauley, 2009, pp. 21, 61–63.

- ↑ Pauley, 2009, pp. 14–18.

- ↑ Pauley, 2009, pp. 39–52.

- ↑ Pauley, 2009, p. 25.

- ↑ Dik Allen Daso, Doolittle: Aerospace Visionary; Washington: Potomac Books, 2003, p. 4.

- ↑ Pauley, 2009, 59.

- ↑ Pauley, 2009, p. 7.

Sources

- Aeroplane gossip. The Washington Post, Jan 9, 1910, page A15

- Hatfield, 1976, p. 149

- Chronicle of Aviation, p80

- 1910 Los Angeles International Air Meet at Dominguez Field on English Wikipedia

| Event names | Dominguez Field/LA, Dominguez Field exhibition, Los Angeles International Air Meet |

|---|---|

| Event type | exhibition |

| Country | US |

| Locations | Los Angeles |

| Start date | 1910-01-10 |

| Number of days | 11 |

| Tech focus | Airplane, LTA, Photography |

| Participants |